In the fall of 2019, my third graders excavated many artifacts from under the closet of classroom #310. One item was a scrap of paper with the name HOWARD MATIS written on it.

We were able to connect with Howard, a physicist in California who had attended kindergarten in our building over sixty years earlier.

Howard was delighted at the opportunity to connect with current students in our building, and we arranged a video call. Because Howard had grown up in Stuyvesant Town, I prepared a brief lesson on the history of that community, which is only a couple of blocks from our school.

What grabbed my students the most was the shocking (to them) revelation that at its inception, in the late 1940s, Stuy Town—built to house returning WWII vets—would rent apartments only to white people. This was an explicitly stated policy announced by Metropolitan Life Insurance, which developed and owned Stuy Town. How was this possible? my students wondered. And how had it changed?

We dived into these questions and learned a lot. We found out that at the time, it was legal for landlords to discriminate on the basis of race. We learned that a group of Black veterans had sued Met Life, and lost. And we found out that most of the early white residents were actually opposed to this policy, and some of them had worked very hard to change it. Because of the students’ interest, I tracked down a former Stuy Town resident, Liz Fox, whose parents, Lenny and Diana Miller, had been among these activist tenants. She visited our class and we got an eyewitness view of the protests from her. We even got to see the eviction notice that Met Life had sent her parents because they were seen as troublemakers!

My students were really surprised that they had never heard of this before, even those who actually lived in Stuy Town. Most of their parents were also unaware of this history. So we began to think about how we could share this important story. Not only was it a crucial moment in neighborhood history, but it also is now considered to have ignited the protests and legislative efforts that ultimately led to the banning of racial discrimination in housing. First, we created and performed a play at our annual Martin Luther King, Jr., Day presentation. Next, we began to consider the idea of a permanent memorial at Stuy Town that would teach residents and passersby the integration story.

Students worked with small groups to design a memorial to be built at Stuy Town, and write an explanation of their idea. We then invited Rick Hayduk, the manager of Stuy Town, to visit our class, and he enthusiastically listened to my students’ comments, looked carefully at their memorial ideas, and agreed that a memorial should be built! We planned a trip to Stuy Town to scout possible locations for a memorial—and then the pandemic hit.

To make a long story short, the decision to build a permanent memorial was rescinded by Rick’s successor, based on a variety of factors. Stuy Town’s 75th anniversary celebrations in the summer of 2022 made no mention of the integration story at all. My former students, now fifth graders, have written a petition to try to revive the idea of a permanent memorial. Please scroll below to see their memorial designs and a link to sign their petition.

To learn more about the history of Stuyvesant Town, you may want to listen to the Bowery Boys’ episode entitled “Building Stuyvesant Town, the housing solution that became an emblem of the Jim Crow North.” To learn about the Gas House District, which was demolished in order to make room for Stuy Town, check out this historical essay from New York University’s Glucksman Ireland House. And the Bowery Boys also have a podcast about a more recent development in Stuy Town, the fight to preserve middle-income housing.

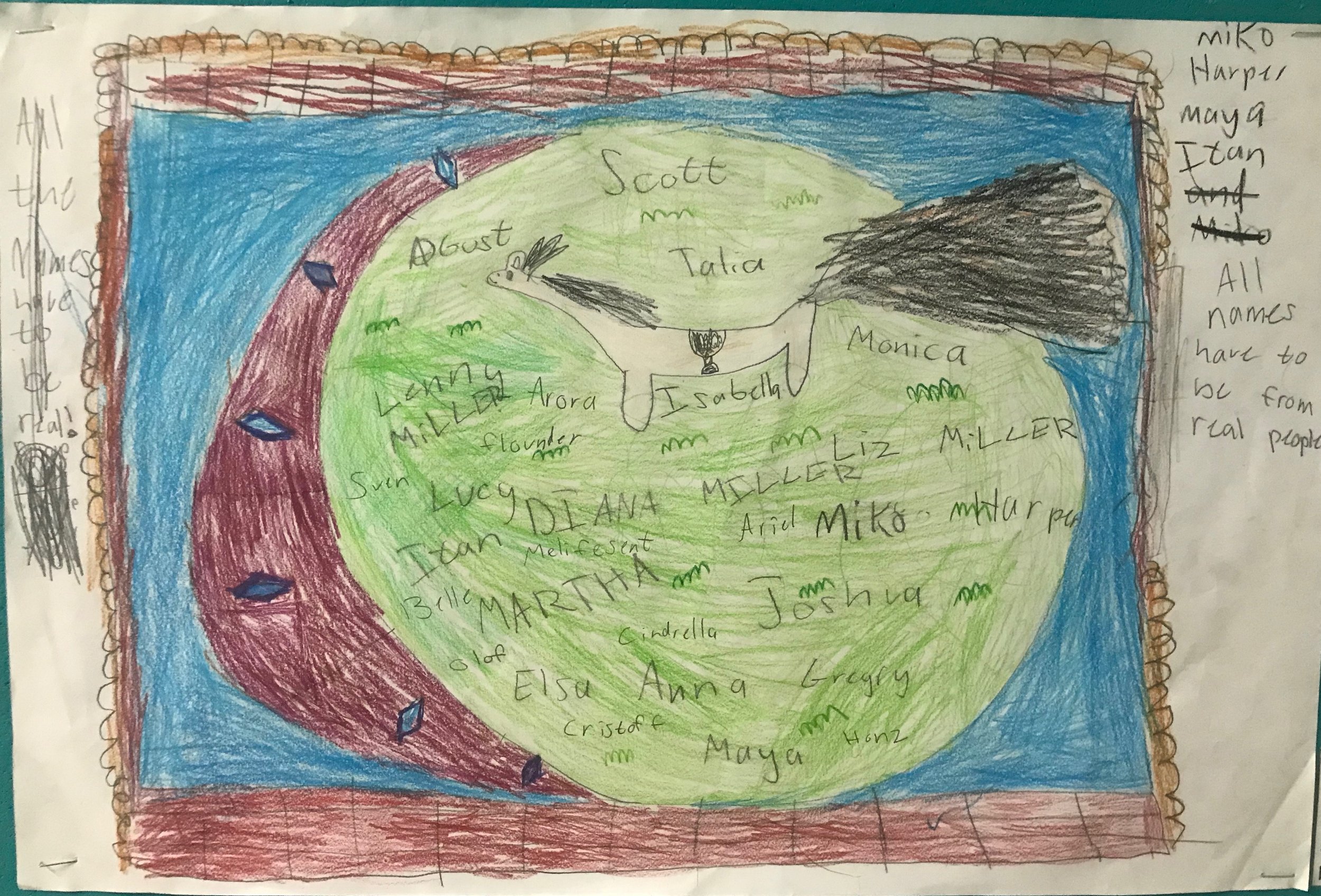

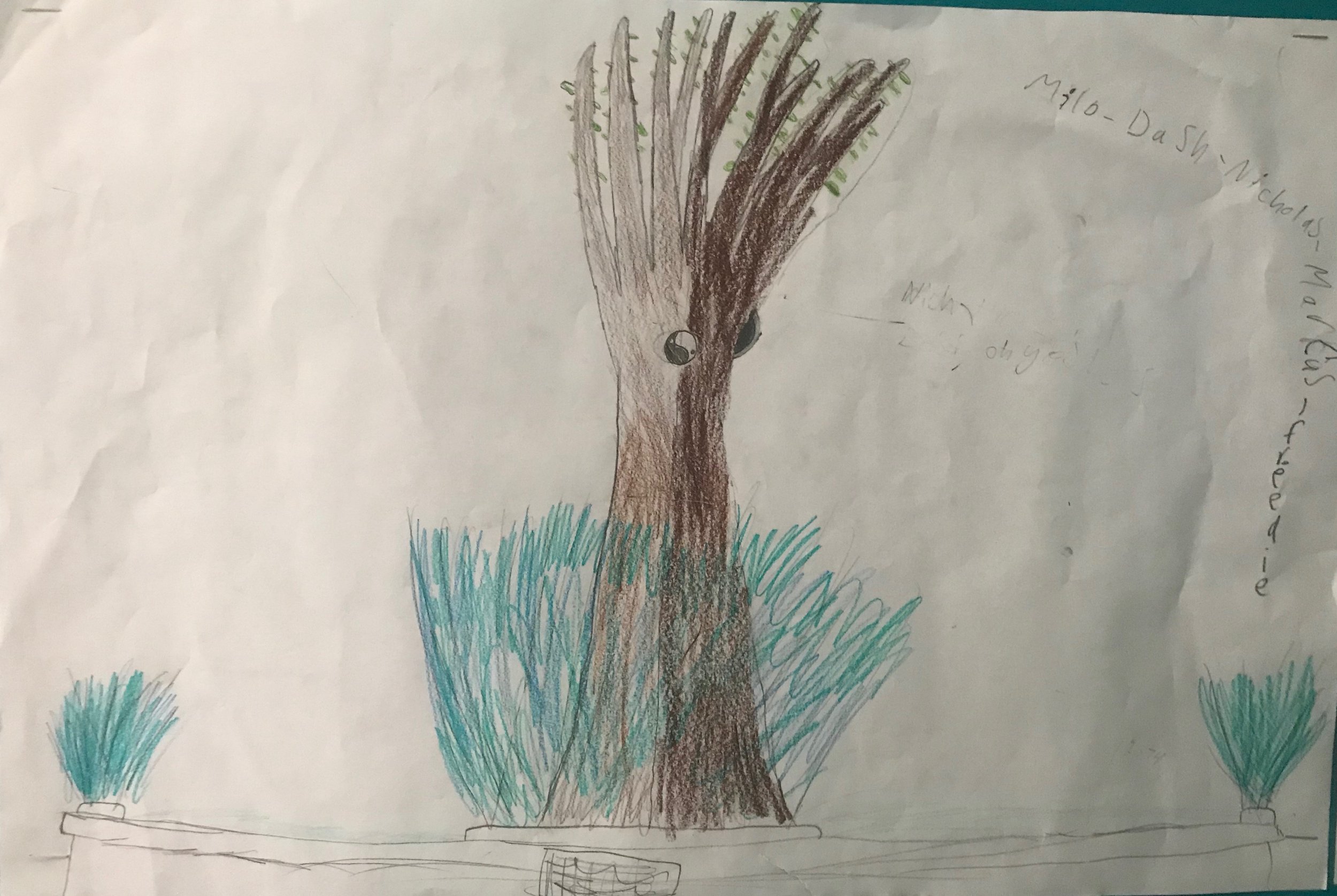

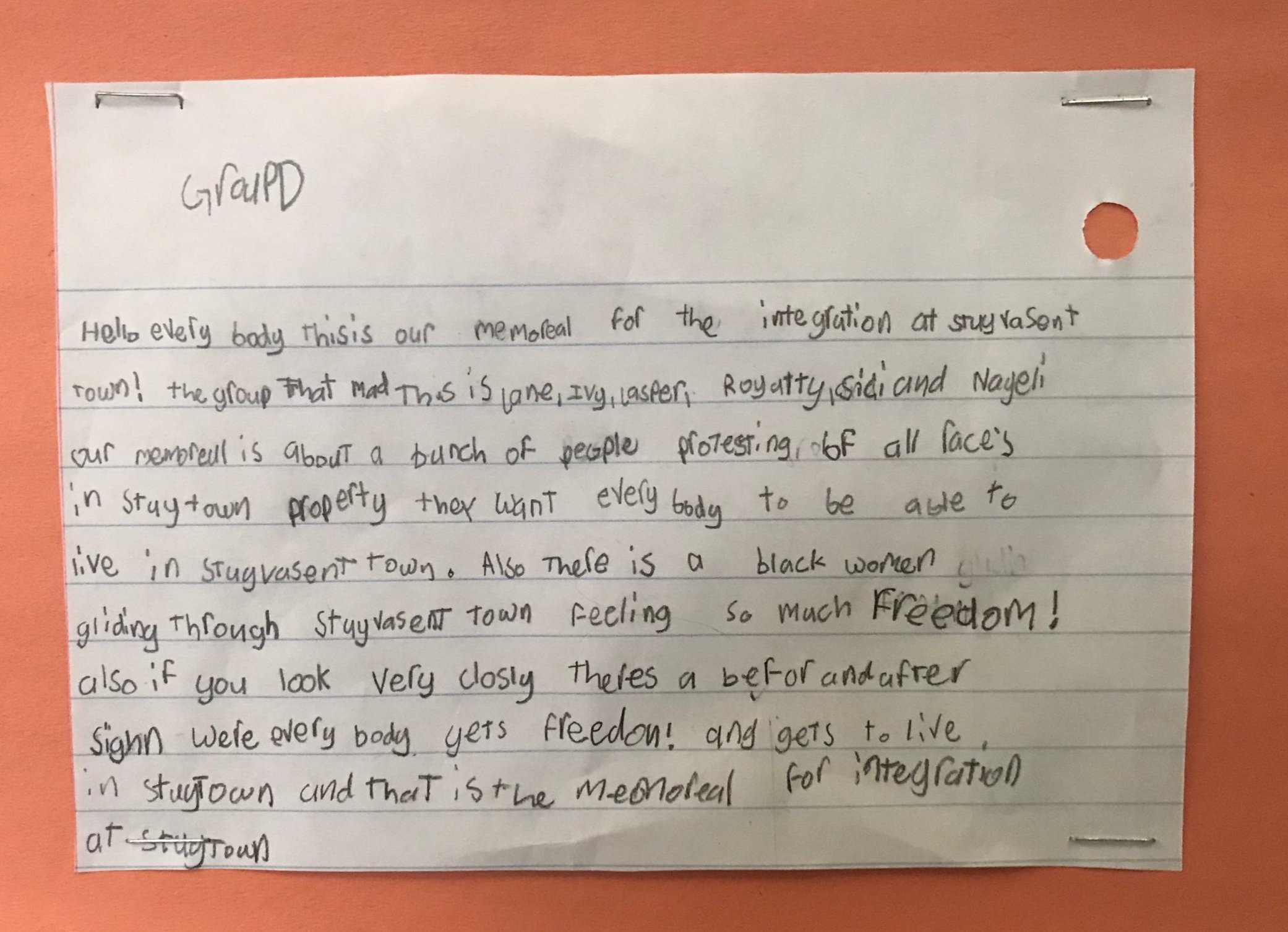

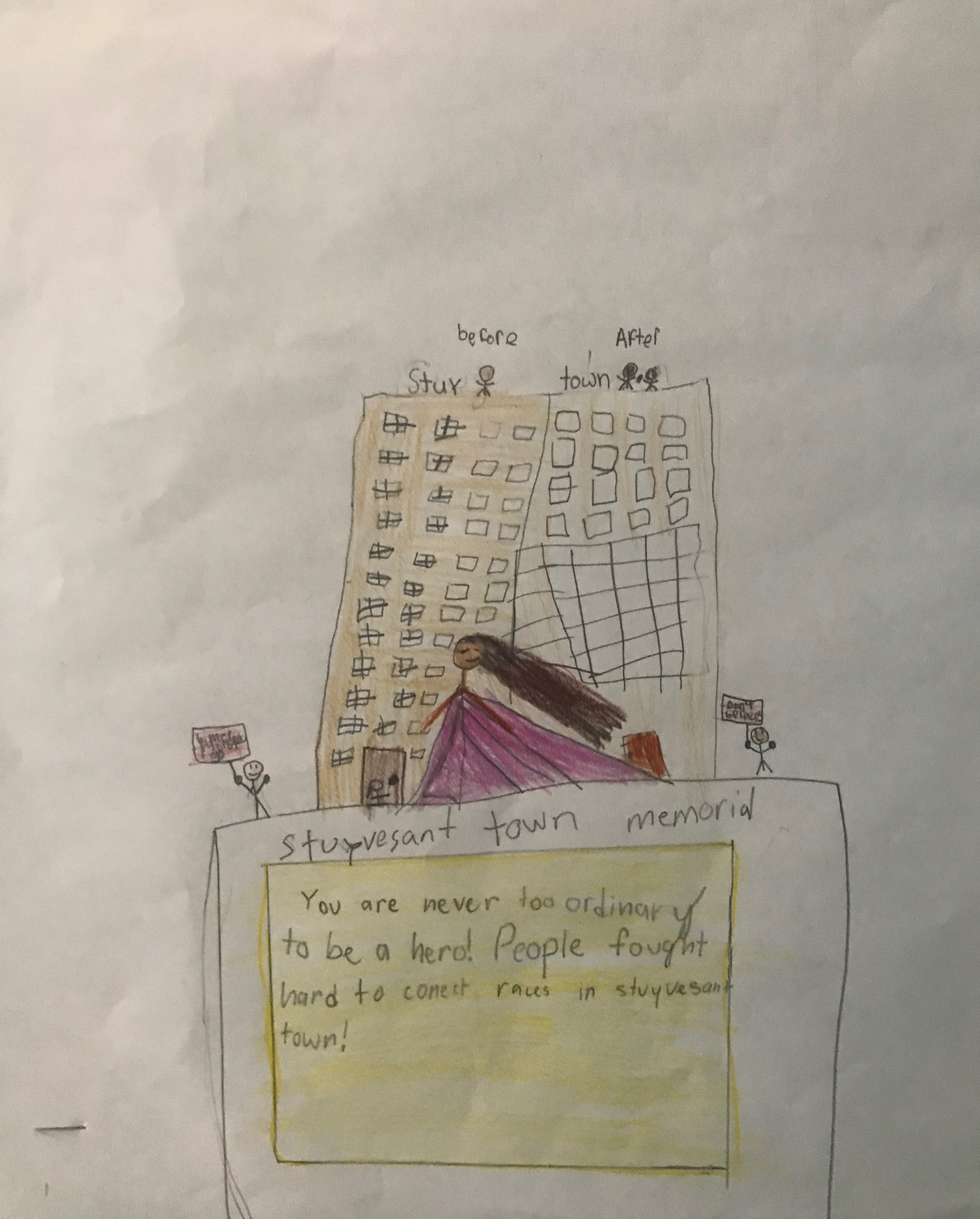

Class Memorial Presentations

Group A Description

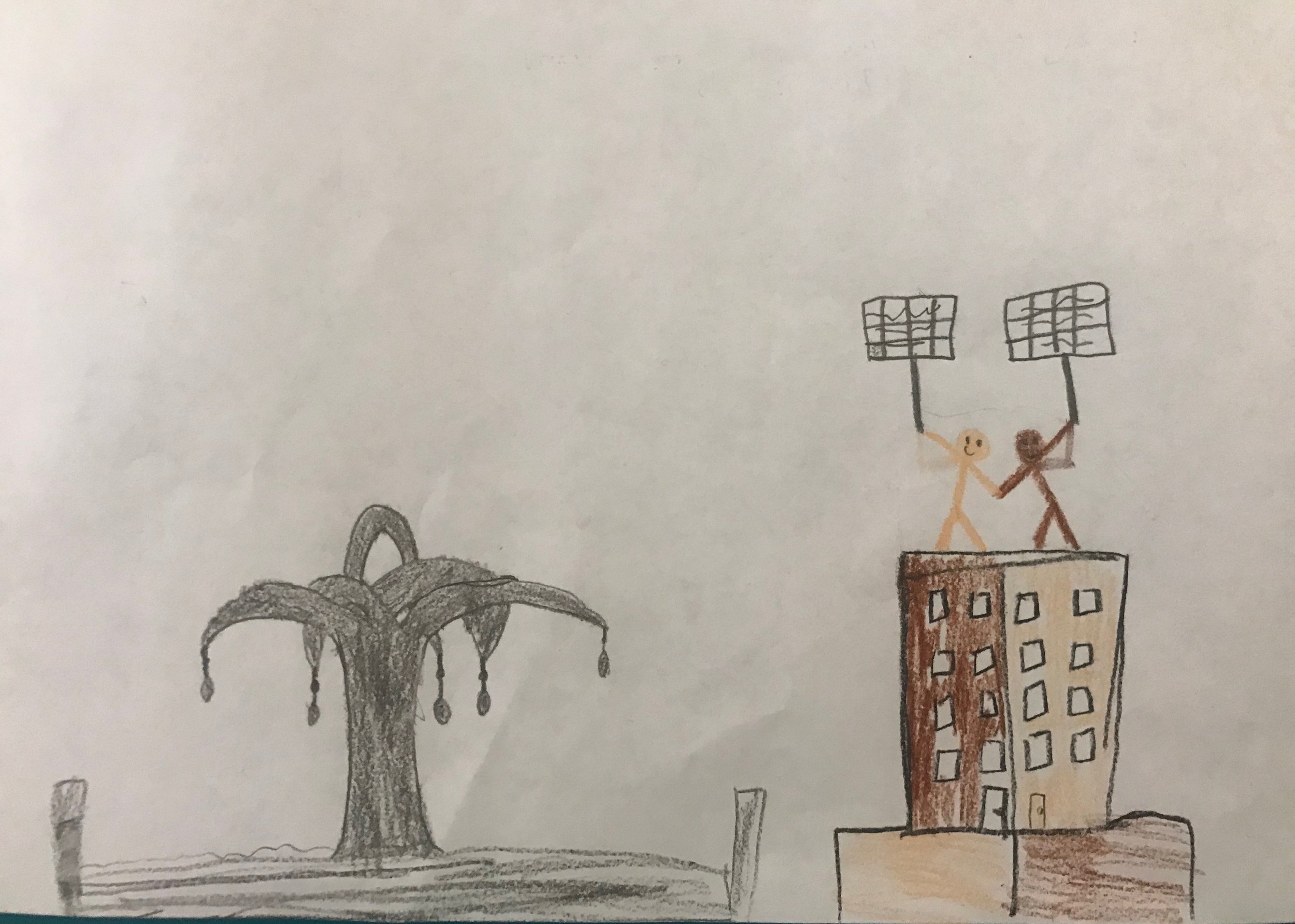

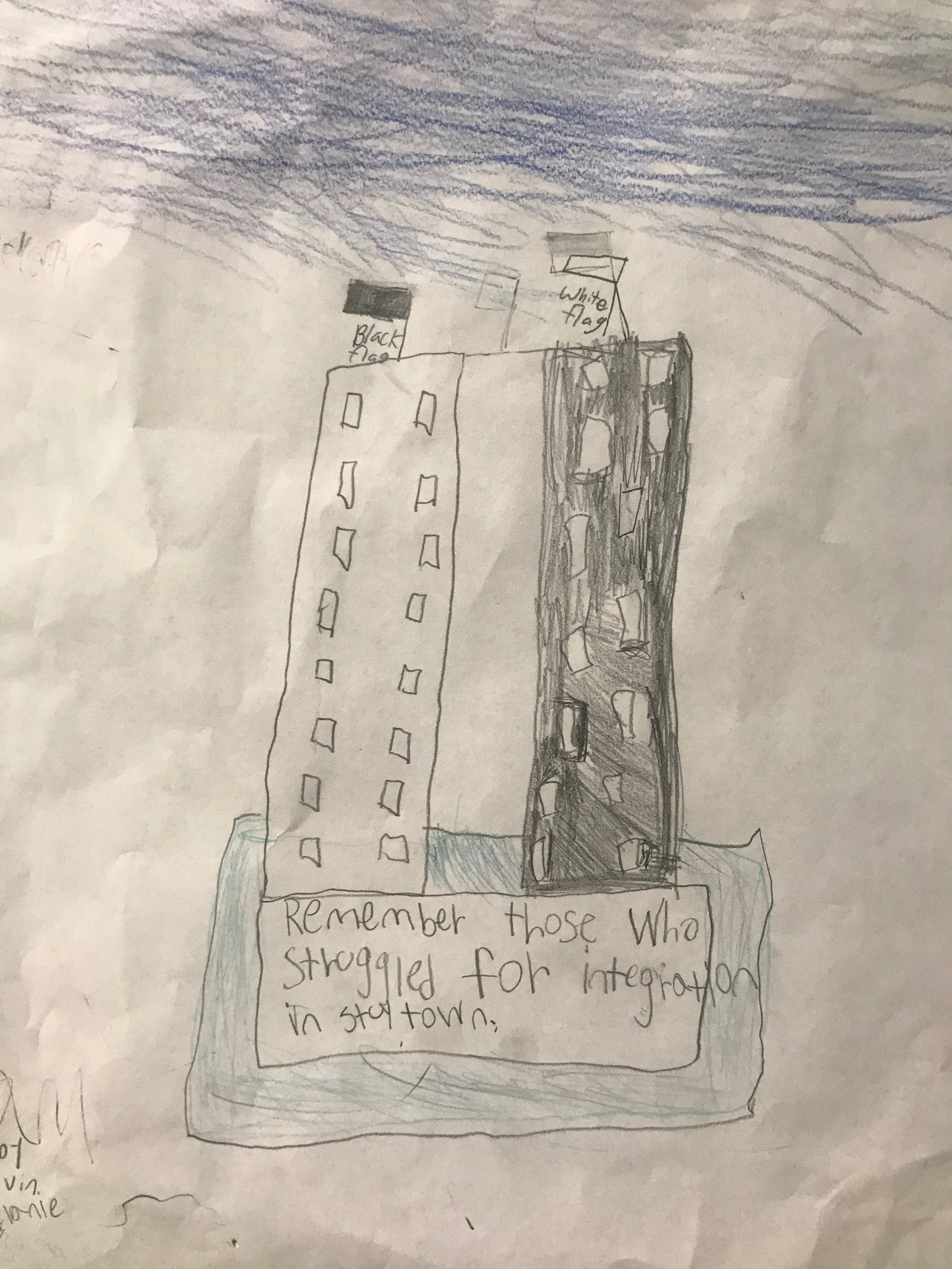

Group A Design

Group B Description

Group B Design

Group C Description

Group C Design

Group D Description

Group D Design

Group E Description

Group E Design

Group U Description

Group U Design

Group V Description

Group V Design

Group W Description

Group W Design

Group X Description

Group X Design

Group Y Description

Group Y Design

Group Z Description

Group Z Design